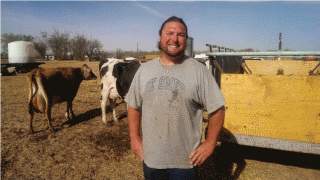

Mike De Smet is known for his friendly disposition, his inability to say no to a challenge, and a deeply ingrained love of dairy farming. De Smet grew up on the 125-acre dairy farm he now manages. But this is not his father’s dairy—he and his wife, Erica, have embarked on an ambitious and pioneering effort to build New Mexico’s first, and only, USDA certified organic, raw, grass fed dairy farm.

De Smet started learning the dairy trade as soon as he was big enough to work in the barn. Like many children of farming families, he was encouraged to go to college and seek a career off the farm. In college in Florida, Mike found himself skipping class to go help in the dairy barns at the university. He says after several times of opting out of his collegial responsibilities to help with artificial insemination, he realized just how much he loved being a dairy farmer.

De Smet started learning the dairy trade as soon as he was big enough to work in the barn. Like many children of farming families, he was encouraged to go to college and seek a career off the farm. In college in Florida, Mike found himself skipping class to go help in the dairy barns at the university. He says after several times of opting out of his collegial responsibilities to help with artificial insemination, he realized just how much he loved being a dairy farmer.

Seven years ago, the 36-year-old third generation dairy farmer decided to return home to help his father manage the family farm. De Smet conducted an informal market survey posting a pasteurized and a raw milk label through his Facebook page. When the raw milk label hit over 4000 likes and the pasteurized only several dozen, he knew what product to pursue. Undaunted by the paperwork or technical requirements he needed to navigate to become a USDA certified organic, raw milk producer, and despite skepticism of fellow dairymen and financial advisers, De Smet built a raw milk dairy. For insurance purposes, and just to be safe, he purchased a pasteurizer, which, he laughs, he still has never turned on.

Perhaps most important, De Smet saw raw dairy production as a way to develop a sustainable business that capitalized on generations of knowledge, kept his family land in production, and built healthy soil that could support farming for generations to come. In the first few years after his return, in addition to hops, De Smet grew feed crops. For the past decade, each year has been drier than the previous, and each field has yielded fewer cuttings, or no crop at all. He knew he needed to get creative to do more with less water.

Perhaps most important, De Smet saw raw dairy production as a way to develop a sustainable business that capitalized on generations of knowledge, kept his family land in production, and built healthy soil that could support farming for generations to come. In the first few years after his return, in addition to hops, De Smet grew feed crops. For the past decade, each year has been drier than the previous, and each field has yielded fewer cuttings, or no crop at all. He knew he needed to get creative to do more with less water.

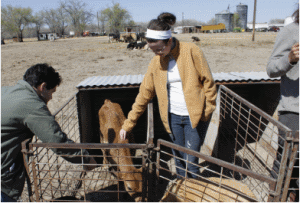

Rather than export the water by way of cutting cash crops to sell to other dairies, he invested in his own herd. De Smet decided to produce all the feed for his dairy on his own farm. He prioritizes the health of his animals and the sustainability of his farm. He milks only once a day, and all his cows, including an additional dozen animals he raises for meat to feed family and friends, graze freely and are entirely grass fed.

Over the next five years, De Smet will grow his dairy to full capacity, about 100 cows. Several factors influence the future size of his herd and the operation—the number of cows he can handle and still ensure that his product is safe and clean, the land it takes to feed his cows, and of course, the water it takes to grow their food.

Most farmers in New Mexico flood irrigate with surface water managed through districts along the Rio Grande. Water availability is increasingly erratic due to very low annual snowpack in the basins that feed the river, and intense monsoons dumping unprecedented amounts of water. At the beginning of 2013, central New Mexico farmers faced the driest season in a century. In September 2013, the Middle Rio Grande saw over three inches of rain—about a third of the area’s average rainfall—in less than a week. For farmers like De Smet this meant that crops went from dying of thirst to drowning in a matter of hours. This year he will try every trick in the book, and invent a few of his own, to anticipate both drought and floods.

The solution to less water is building healthy, resilient soil. Working with a forage specialist through the extension agency, De Smet has moved to no-till planting methods and has begun experimenting with cycling nutrients in his fields. Carefully dividing up the acreage, he plants some fields in cool season grasses, and others in warm season grasses, so the fields will be fully productive at different times over the course of the season, allowing him to move the herd to a new paddock every day. The key, he says, is making sure the earth is never bare. Unlike the fields he still disks, plows, and plants in a more conventional way, the no-till fields show moisture less than a half-inch below the soil’s surface.

De Smet plans to double his herd size in the next year, but he hesitates, “It all depends on water.” Even though his growing practices have increased the moisture, humus, and mycorrhizal levels of the soil, he knows there’s only so much forage the field will produce without water. De Smet knows farming carries no guarantees, like how many days of water the river will provide, but he faces his challenges with bravery, perseverance, and laughter.

Additional Resources:

Soil Quality & Nutrient Cycling: soilquality.org/functions/nutrient_cycling.html

New Mexico Department of Agriculture Organic Program: www.nmda.nmsu.edu/marketing/organic-program/

Western SARE Crop Rotation: westernsare.org/Learning-Center/Books/Crop-Rotation-on-Organic-Farms

Western SARE Dairy Soil Health: http://www.westernsare.org/Learning-Center/FactSheets/National-SARE-Fact-Sheets/Alternative-Continuous-Cover-Dairy-Forage-System-for-ProfitabilityFlexibility-and-Soil-Health